Overview

In this lesson, students will examine the role of Miranda rights in safeguarding individual civil liberties and rights.

In this lesson, students will examine the role of Miranda rights in safeguarding individual civil liberties and rights.

Recommended to have completed Lesson 1: The Boston Massacre and Due Process. Optional is also to read pages 80–105 of the Kerner Commission report.

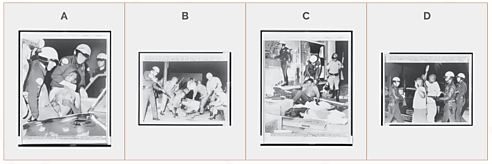

Step 1: Describe to students that they will be using visual literacy skills to analyze what is happening in the following photographs.

Figure 2: Police Removing Black Demonstrators Suspected of Breaking the Law in 1965 in Los Angeles. (A) Carrying Suspect into Car, (B) Police and National Guardsmen Waiting at a Manhole after Dropping Tear Gas Inside, (C) Dragging a Young Man from a Storefront, (D) Marching Two Men from the Los Angeles Black Muslim Mosque.

Step 2: Provide students with the table in Handout 1 to fill in their answers as to who, what, when, where, and why of what they think is happening in the pictures.

Step 3: Have students share as a class after they have had a few minutes to individually record their initial thoughts.

Step 4: Share that the photographs at the beginning of this lesson capture the abuses of a pre‐Miranda rights world. Many individuals were denied adequate representation or bail. Writing for the majority in 1966, one year after the Watts riot/rebellion, US Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren lauded the most fundamental of civil liberties in Miranda v. Arizona:

“The constitutional foundation underlying the privilege is the respect a governmen—state or federal—must accord to the dignity and integrity of its citizens.… To permit a full opportunity to exercise the privilege against self‐incrimination, the accused must be adequately and effectively apprised of his rights and the exercise of those rights must be fully honored.”

Explain to students that they will examine the case of Miranda v. Arizona and how this became a pivotal discussion about constitutional civil liberties and rights.

Step 1: Read pages 4, 6, and 7 of the Kerner Commission report (1967), which was put together after riots took place in metropolitan areas around the country.

Step 2: As a class, have students turn to Chapter 2. If you chose to have students read the chapter on their own, engage in a discussion with them about what they learned regarding what the government was concerned about, what was occurring, and the solutions being suggested at the time. Otherwise, have students learn about the chapter with you facilitating the discussion after going over the following summary.

Summarize for students that in Chapter 2 the authors identify the following sequence:

discrimination, prejudice, disadvantaged conditions, intense and pervasive grievances, a series of tension‐heightening incidents.” This sequence culminates “in the eruption of disorder at the hands of youthful, politically‐aware activists.

Social and economic grievance is quickly reframed as political protest, and law enforcement action veers in the direction of quashing dissent. Trials in this reframed context place a spotlight on state action in the face of unlawful assembly and destruction of property.

Step 3: Pause here and ask students. What civil liberties and civil rights should alleged offenders receive?

After students engage in discussion, share that of particular interest is the Kerner report’s account on the discriminatory administration of justice in the metropolitan areas that experienced civil disturbances:

Eight of the prior incidents involved cases of allegedly discriminatory administration of justice. Typical was a case in Houston a month‐and‐a‐half before the disorder. Three civil rights advocates were arrested for leading a protest and for their participation in organizing a boycott of classes at the predominantly Negro Texas Southern University. Bond was set at $25,000 each. The court refused for several days to reduce bond, even though TSU officials dropped the charges they had originally pressed. There were no final incidents identified involving the administration of justice. In a unique case in New Haven, the shooting of a Puerto Rican by a white man was identified as the final incident before violence. Finally, we have noted a marked relationship between prior and final incidents within each city. In most of the cities surveyed, the final incident was of the same type as one or more of the prior incidents. For example, police actions were identified as both the final incident and one or more prior incidents preceding seven disturbances. Rallies or meetings to protest police actions involved in a prior incident were identified as the final incident preceding three additional disturbances. The cumulative reinforcement of grievances and heightening of tensions found in all instances were particularly evident in these cases.

Adequate representation would require the introduction of evidence of police provocation as a precipitating factor for some of the arrests. Indigent defendants would be at a disadvantage were they to represent themselves in situations where their participation in a protest (that devolved into a riot) could not be contextualized. As we saw in the opening lesson on the complexities of the Boston Massacre, unlawful assembly can quickly escalate into widespread violence against persons and property, with multiple innocent bystanders caught in the rapid sweep of events.

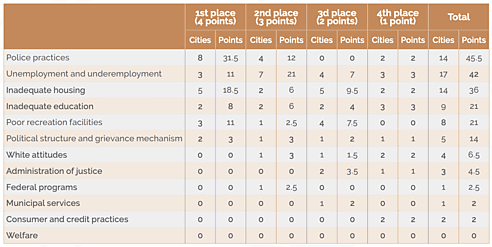

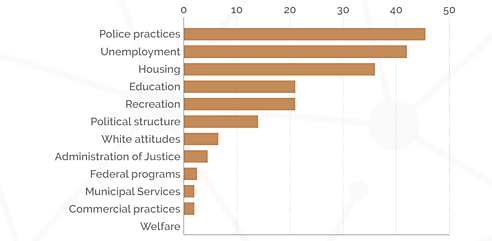

Our focus next shifts to the prioritization of grievances as represented by these charts on page 100 of the Kerner report to highlight the perception of a link between police practices and the intensity of civil disorder that resulted in mass arrests.

The total of points for each category is the product of the number of cities times the number of points indicated at the top of each double column, except where two grievances were judged equally serious. In these cases, the total points for the two rankings involved were divided equally (e.g., in case two were judged equally suitable for the first priority, the total points for the first and second were divided, and each received 3.5 points).

*See right‐hand corner of Part 1.

We return to the specific context of the Watts riot/rebellion with the closing activity and the closer examination of Bayard Rustin’s The Watts Manifesto and the McCone Report.

Step 5: Revisit the question you prompted students with and ask them if any of their initial thoughts changed and how so.

Step 1: Have students in pairs read Miranda v. Arizona.

Step 2: Ask students to fill out the case section in Handout 2.

Step 3: Engage students in a Socratic seminar about the following:

Translate the Miranda warning into a foreign language of your choice using Google Translate. How often do you think suspects receive a Miranda warning in the language you chose?

Do you understand the rights I have just read to you? With these rights in mind, do you wish to speak to me?