The OpenStax textbook American Government 3e contains pertinent information to contextualize many of the lessons in this unit. Depending on your curriculum needs, student reading level and access to technology, and time allotment for student homework, this text is a great complement to the unit lessons. Below, you will find suggested chapters that may be used independently or in sequence with the lessons in the unit. The author of the lessons has also provided a pairing summary for each reading that is a great addition for students who might need extra support. Additionally, you will find a pairing annotation guide students may use to help them do a close read of the text.

Overview

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- The Constitution simply refers to “persons,” which over time has grown to mean that even children, visitors from other countries, and immigrants—permanent or temporary, legal or undocumented—enjoy the same freedoms when they are in the United States or its territories as adult citizens do.

- The Eighth Amendment says the government cannot impose “cruel and unusual punishments” on individuals for their criminal acts. Although the definitions of cruel and unusual have expanded over the years, the courts have generally and consistently interpreted this provision as making it unconstitutional for government officials to torture suspects.

- In Article I, Section 9, the Constitution limits the power of Congress in three ways: prohibiting the passage of bills of attainder, prohibiting ex post facto laws, and limiting the ability of Congress to suspend the writ of habeas corpus.

- Soon after slavery was abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment, state governments— particularly those in the former Confederacy—began to pass “Black codes” that restricted the rights of formerly enslaved people, including the right to hold office, own land, or vote, relegating them to second‐class citizenship.

- With the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, the scope and limits of civil liberties became clearer. First, the amendment says, “no State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States,” which is a provision that echoes the privileges and immunities clause in Article IV, Section 2 of the original Constitution ensuring that states treat citizens of other states the same as their own citizens.

- The second provision of the Fourteenth Amendment pertaining to the application of the Bill of Rights to the states is the due process clause, which famously reads, “nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Like the Fifth Amendment, this clause refers to “due process,” a term that is interpreted to require both access to procedural justice (such as the right to a trial) as well as the more substantive implication that people be treated fairly and impartially by government officials.

- Beginning in 1897, the Supreme Court has found that various provisions of the Bill of Rights protecting these fundamental liberties must be upheld by the states, even if their state constitutions and laws (and the Tenth Amendment itself) do not protect them as fully as the Bill of Rights does—or at all. This means there has been a process of selective incorporation of the Bill of Rights into the practices of the states.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- The Fifth Amendment also protects individuals against double jeopardy, a process that subjects a suspect to prosecution twice for the same criminal act. No one who has been acquitted (found not guilty) of a crime can be prosecuted again for that crime. But the prohibition against double jeopardy has its own exceptions. The most notable is that it prohibits a second prosecution only at the same level of government (federal or state) as the first; the federal government can try you for violating federal law, even if a state or local court finds you not guilty of the same action.

- People have the right not to give evidence in court or to law enforcement officers that might constitute an admission of guilt or responsibility for a crime. Moreover, in a criminal trial, if someone does not testify in their own defense, the prosecution cannot use that failure to testify as evidence of guilt or imply that an innocent person would testify. This provision became embedded in the public consciousness following the Supreme Court’s 1966 ruling in Miranda v. Arizona, whereby suspects were required to be informed of their most important rights, including the right against self‐incrimination, before being interrogated in police custody. However, contrary to some media depictions of the Miranda warning, law enforcement officials do not necessarily have to inform suspects of their rights before they are questioned in situations where they are free to leave.

- Like the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, the Fifth Amendment prohibits the federal government from depriving people of their “life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” Recall that due process is a guarantee that people will be treated fairly and impartially by government officials when the government seeks to fine or imprison them or take their personal property away from them. The courts have interpreted this provision to mean that government officials must establish consistent, fair procedures to decide when people’s freedoms are limited. In other words, citizens cannot be detained, their freedom limited, or their property taken arbitrarily or on a whim by police or other government officials.

- The takings clause says that “private property [cannot] be taken for public use, without just compensation.” This provision, along with the due process clause’s provisions limiting the taking of property, can be viewed as a protection of individuals’ economic liberty: their right to obtain, use, and trade tangible and intangible property for their own benefit.

- Civil forfeiture was a mainstay of the war on drugs and contributed to the mass incarceration of people of color. It can be economically damaging even for those who are never charged or convicted, because in many cases seized property is not returned to its owner.

- Most people accused of crimes decline their right to a jury trial. This choice is typically the result of a plea bargain, an agreement between the defendant and the prosecutor in which the defendant pleads guilty to the charge(s) in question, or perhaps to less serious charges, in exchange for more lenient punishment than they might receive if convicted after a full trial.

- The Sixth Amendment guarantees the right of those accused of crimes to present witnesses in their own defense (if necessary, compelling them to testify) and to confront and cross‐examine witnesses presented by the prosecution. In general, the only testimony acceptable in a criminal trial must be given in a courtroom and be subject to cross‐examination; hearsay, or testimony by one person about what another person has said, is generally inadmissible, although hearsay may be presented as evidence when it is an admission of guilt by the defendant or a “dying declaration” by a person who has passed away.

- Bail is a payment of money that allows a person accused of a crime to be freed pending trial. If you “make bail” in a case and do not show up for your trial, you will forfeit the money you paid. Since many people cannot afford to pay bail directly, they may instead get a bail bond, which allows them to pay a fraction of the money (typically 10 percent) to a person who sells bonds and who pays the full bail amount. (In most states, the bond seller makes money because the defendant does not get back the money for the bond, and most people show up for their trials.)

- The most controversial provision of the Eighth Amendment is the ban on “cruel and unusual punishments.” Various torturous forms of execution common in the past—drawing and quartering, burning people alive, and the electric chair—are prohibited by this provision.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- Supporters of a broad interpretation of the Ninth Amendment point out that the rights of the people—particularly people belonging to political or demographic minorities—should not be subject to the whims of popular majorities.

- The federal government has both enumerated and implied powers, but where the federal government does not (or chooses not to) exercise power, the states may do so.

- At times, politicians and state governments have argued that the Tenth Amendment means states can engage in interposition or nullification by blocking federal government laws and actions they deem to exceed the constitutional powers of the national government.

- However, the Tenth Amendment also allows states to guarantee rights and liberties more fully or extensively than the federal government does, or to include additional rights. For example, many state constitutions guarantee the right to a free public education and several states give victims of crimes certain rights.

- In the United States, many advocates of civil liberties are concerned that laws such as the USA Patriot Act (i.e., Uniting and Strengthening America by Providing Appropriate Tools Required to Intercept and Obstruct Terrorism Act), passed weeks after the 9/11 attacks in 2001, have given the federal government too much power by making it easy for officials to seek and obtain search warrants or, in some cases, to bypass warrant requirements altogether.

- In Carpenter v. United States (2018), the first case of its kind, the US Supreme Court ruled that, under the Fourth Amendment, police need a search warrant to gather phone location data as evidence to be used in trials.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- … in the case Dred Scott v. Sandford, the justices rejected Scott’s argument that though he had been born into slavery, his time spent in free states and territories where slavery had been banned by the federal government had made him a free man. In fact, the Court’s majority stated that Scott had no legal right to sue for his freedom at all because Black people (whether free or enslaved) were not, and could not become, US citizens.

- Perhaps the most famous of the tools of disenfranchisement were literacy tests and understanding tests. Literacy tests, which had been used in the North since the 1850s to disqualify naturalized European immigrants from voting, called on the prospective voter to demonstrate his (and later, her) ability to read a particular passage of text. However, since voter registration officials had discretion to decide what text the voter was to read, they could give easy passages to voters they wanted to register (typically, white people) and more difficult passages to those whose registration they wanted to deny (typically, Black people).

- Some states introduced a loophole, known as the grandfather clause, to allow less literate white people to vote. The grandfather clause exempted those who had been allowed to vote in that state prior to the Civil War and their descendants from literacy and understanding tests.24 Because Black people were not allowed to vote prior to the Civil War, but most White men had been voting at a time when there were no literacy tests, this loophole allowed most illiterate white people to vote.

- In states where the voting rights of poor white people were less of a concern, another tool for disenfranchisement was the poll tax (Figure 5.6). This was an annual per‐person tax, typically one or two dollars (on the order of $20 to $50 today), that a person had to pay to register to vote.

- Although these methods were usually sufficient to ensure that Black people were kept away from the polls, some dedicated African Americans did manage to register to vote despite the obstacles placed in their way. To ensure their vote was largely meaningless, the White elites used their control of the Democratic Party to create the white primary: primary elections in which only White people were allowed to vote. The state party organizations argued that as private groups, rather than part of the state government, they had no obligation to follow the Fifteenth Amendment’s requirement not to deny the right to vote on the basis of race.

- In Virginia, state leaders employed a strategy of “massive resistance” to school integration, which led to the closure of a large number of public schools across the state, some for years.34 Although de jure segregation, segregation mandated by law, had ended on paper, in practice, few efforts were made to integrate schools in most school districts with substantial Black student populations until the late 1960s.

- In 1962, Congress proposed what later became the Twenty‐Fourth Amendment, which banned the poll tax in elections to federal (but not state or local) office; the amendment went into effect after being ratified in early 1964. Several southern states continued to require residents to pay poll taxes in order to vote in state elections until 1966 when, in the case of Harper v. Virginia Board of Elections, the Supreme Court declared that requiring payment of a poll tax in order to vote in an election at any level was unconstitutional.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- The specific delegated or expressed powers granted to Congress and to the president were clearly spelled out in the body of the Constitution under Article I, Section 8, and Article II, Sections 2 and 3.

- In addition to these expressed powers, the national government was given implied powers that, while not clearly stated, are inferred. These powers stem from the elastic clause in Article I, Section 8, of the Constitution, which provides Congress the authority “to make all Laws which shall be necessary and proper for carrying into Execution the Foregoing powers.”

- The states were given a host of powers independent of those enjoyed by the national government. As one example, they now had the power to establish local governments and to account for the structure, function, and responsibilities of these governments within their state constitutions. This gave states sovereignty, or supreme and independent authority, over county, municipal, school and other special districts.

- The Tenth Amendment was included in the Bill of Rights to create a class of powers, known as reserved powers, exclusive to state governments. The amendment specifically reads, “The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people.” In essence, if the Constitution does not decree that an activity should be performed by the national government and does not restrict the state government from engaging in it, then the state is seen as having the power to perform the function.

- Besides reserved powers, the states also retained concurrent powers, or responsibilities shared with the national government. As part of this package of powers, the state and federal governments each have the right to collect income tax from their citizens and corporate tax from businesses. They also share responsibility for building and maintaining the network of interstates and highways and for making and enforcing laws.

- States have been granted the flexibility to set policy across a number of controversial policy areas. For instance, a wide array of states require parental consent for abortions performed on minors, ban abortions completely or after a certain number of weeks of pregnancy, or require patients to undergo an ultrasound before the procedure. As another example, currently, almost half the states allow for the use of medical marijuana and sixteen more states have fully legalized it, despite the fact that this practice stands in contradiction to federal law that prohibits the use and distribution of marijuana.

- Through their own constitutions and statutes, states decide what to require of local jurisdictions and what to delegate. This structure represents the legal principle of Dillon’s Rule, named for Iowa Supreme Court justice John F. Dillon. Dillon argued that state actions trump those of the local government and have supremacy.10 In this view, cities and towns exist at the

- Given the necessity of cooperation, many states have granted local governments some degree of autonomy and given them discretion to make policy or tax decisions. This added independence is called home rule, and the transfer of power is typically spelled out within a charter. Charters are similar to state constitutions: they provide a framework and a detailed accounting of local government responsibilities and areas of authority.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- Most citizens base their political opinions on their beliefs and their attitudes, both of which begin to form in childhood. Beliefs are closely held ideas that support our values and expectations about life and politics.

- Our attitudes are also affected by our personal beliefs and represent the preferences we form based on our life experiences and values. A person who has suffered racism or bigotry may have a skeptical attitude toward the actions of authority figures, for example.

- Over time, our beliefs and our attitudes about people, events, and ideas will become a set of norms, or accepted ideas, about what we may feel should happen in our society or what is right for the government to do in a situation. In this way, attitudes and beliefs form the foundation for opinions.

- Political socialization is the process by which we are trained to understand and join a country’s political world, and, like most forms of socialization, it starts when we are very young. We may first become aware of politics by watching a parent or guardian vote, for instance, or by hearing presidents and candidates speak on television or the Internet, or seeing adults honor the American flag at an event.

- Accounting for the process of socialization is central to our understanding of public opinion, because the beliefs we acquire early in life are unlikely to change dramatically as we grow older. Our political ideology, made up of the attitudes and beliefs that help shape our opinions on political theory and policy, is rooted in who we are as individuals.

- Today, polling agencies have noticed that citizens’ beliefs have become far more polarized, or widely opposed, over the last decade. To track this polarization, Pew Research conducted a study of Republican and Democratic respondents over a 25‐year span.

- An agent of political socialization is a source of political information intended to help citizens understand how to act in their political system and how to make decisions on political matters.

- In the United States, one benefit of socialization is that our political system enjoys diffuse support, which is support characterized by a high level of stability in politics, acceptance of the government as legitimate, and a common goal of preserving the system. These traits keep a country steady, even during times of political or social upheaval.

- Another way the media socializes audiences is through framing, or choosing the way information is presented. Framing can affect the way an event or story is perceived. Candidates described with negative adjectives, for instance, may do poorly on Election Day. Consider the recent demonstrations over the deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and of Freddie Gray in Baltimore, Maryland. Both deaths were caused by police actions against unarmed African American men. Brown was shot to death by an officer on August 9, 2014. Gray died from spinal injuries sustained in transport to jail in April 2015. Following each death, family, friends, and sympathizers protested the police actions as excessive and unfair. While some television stations framed the demonstrations as riots and looting, other stations framed them as protests and fights against corruption. The demonstrations contained both riot and protest, but individuals’ perceptions were affected by the framing chosen by their preferred information sources.

- The socialization process leaves citizens with attitudes and beliefs that create a personal ideology. Ideologies depend on attitudes and beliefs, and on the way we prioritize each belief over the others. Most citizens hold a great number of beliefs and attitudes about government action.

- In the United States, ideologies at the right side of the spectrum prioritize government control over personal freedoms. They range from fascism to authoritarianism to conservatism. Ideologies on the left side of the spectrum prioritize equality and range from communism to socialism to liberalism (Figure 6.6). Moderate ideologies fall in the middle and try to balance the two extremes. When thinking about ideology and politics, it is important not to fall into thinking that involves false dichotomies.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- In Federalist No. 10, James Madison warned of the dangers of “factions,” minorities who would organize around issues they felt strongly about, possibly to the detriment of the majority. But Madison believed limiting these factions was worse than facing the evils they might produce, because such limitations would violate individual freedoms. Instead, the natural way to control factions was to let them flourish and compete against each other.

- Madison’s definition of factions can apply to both interest groups and political parties. But unlike political parties, interest groups do not function primarily to elect candidates under a certain party label or to directly control the operation of the government. Political parties in the United States are generally much broader coalitions that represent a significant proportion of citizens. In the American two‐party system, the Democratic and Republican Parties spread relatively wide nets to try to encompass large segments of the population. In contrast, while interest groups may support or oppose political candidates, their goals are usually more issue‐specific and narrowly focused on areas like taxes, the environment, and gun rights or gun control, or their membership is limited to specific professions.

- Definitions abound when it comes to interest groups, which are sometimes referred to as special interests, interest organizations, pressure groups, or just interests. Most definitions specify that interest group indicates any formal association of individuals or organizations that attempt to influence government decisionmaking and/or the making of public policy.

- While influencing policy is the primary goal, interest groups also monitor government activity, serve as a means of political participation for members, and provide information to the public and to lawmakers. According to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 36 states have laws requiring that voters provide identification at the polls. A civil rights group like the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) will keep track of proposed voter‐identification bills in state legislatures that might have an effect on voting rights.

- Interest groups and organizations represent both private and public interests in the United States. Private interests usually seek particularized benefits from government that favor either a single interest or a narrow set of interests.

- On the other hand, public interest groups attempt to promote public, or collective, goods. Such collective goods are benefits—tangible or intangible—that help most or all citizens. These goods are often produced collectively, and because they may not be profitable and everyone may not agree on what public goods are best for society, they are often underfunded and thus will be underproduced unless there is government involvement.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

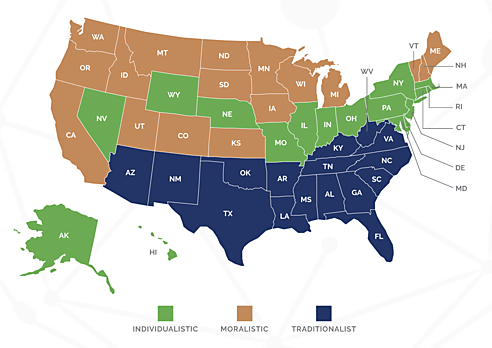

- In the book, American Federalism: A View from the States, Daniel Elazar first theorized in 1966 that the United States could be divided into three distinct political cultures: moralistic, individualistic, and traditionalistic (Figure 14.7). The diffusion of these cultures throughout the United States is attributed to the migratory patterns of immigrants who settled in and spread out across the country from the East Coast to the West Coast. These settlers had distinct political and religious values that influenced their beliefs about the proper role of government, the need for citizen involvement in the democratic process, and the role of political parties.

- Daniel Elazar posited that the United States can be divided geographically into three types of political cultures—individualistic, moralistic, and traditionalistic—which spread with the migratory patterns of immigrants across the country.

- In Elazar’s framework, states with a moralistic political culture see the government as a means to better society and promote the general welfare. They expect political officials to be honest in their dealings with others, put the interests of the people they serve above their own, and commit to improving the area they represent. The political process is seen in a positive light and not as a vehicle tainted by corruption.

- States that identify with this culture value citizen engagement and desire citizen participation in all forms of political affairs. In Elazar’s model, citizens from moralistic states should be more likely to donate their time and/or resources to political campaigns and to vote. This occurs for two main reasons. First, state law is likely to make it easier for residents to register and to vote because mass participation is valued. Second, citizens who hail from moralistic states should be more likely to vote because elections are truly contested. In other words, candidates will be less likely to run unopposed and more likely to face genuine competition from a qualified opponent.

- States that align with Elazar’s individualistic political culture see the government as a mechanism for addressing issues that matter to individual citizens and for pursuing individual goals. People in this culture interact with the government in the same manner they would interact with a marketplace. They expect the government to provide goods and services they see as essential, and the public officials and bureaucrats who provide them expect to be compensated for their efforts. The focus is on meeting individual needs and private goals rather than on serving the best interests of everyone in the community.

- Since this theoretical lens assumes that the objective of politics and the government is to advance individual interests, Elazar argues that individuals are motivated to become engaged in politics only if they have a personal interest in this area or wish to be in charge of the provision of government benefits. They will tend to remain involved if they get enjoyment from their participation or rewards in the form of patronage appointments or financial compensation.

- Given the prominence of slavery in its formation, a traditionalistic political culture, in Elazar’s argument, sees the government as necessary to maintaining the existing social order, the status quo. Only elites belong in the political enterprise, and as a result, new public policies will be advanced only if they reinforce the beliefs and interests of those in power.

- While moralistic cultures expect and encourage political participation by all citizens, traditionalistic cultures are more likely to see it as a privilege reserved for only those who meet the qualifications. As a result, voter participation will generally be lower in a traditionalistic culture, and there will be more barriers to participation (e.g., a requirement to produce a photo ID at the voting booth). Conservatives argue that these laws reduce or eliminate fraud on the part of voters, while liberals believe they disproportionately disenfranchise the poor and minorities and constitute a modern‐day poll tax.

Students will be encouraged to consider several key claims in this pre‐reading.

- •In his classic work, The Logic of Collective Action, economist Mancur Olson discussed the conditions under which collective actions problems would exist, and he noted that they were prevalent among organized interests. People tend not to act when the perceived benefit is insufficient to justify the costs associated with engaging in the action.

- • Collective action problems and free riding occur in many other situations as well. If union membership is optional and all workers will receive a salary increase regardless of whether they make the time and money commitment to join, some workers may free ride. The benefits sought by unions, such as higher wages, collective bargaining rights, and safer working conditions, are often enjoyed by all workers regardless of whether they are members.

- Group leaders also play an important role in overcoming collective action problems. For instance, political scientist Robert Salisbury suggests that group leaders will offer incentives to induce activity among individuals. Some offer material incentives, which are tangible benefits of joining a group. AARP, for example, offers discounts on hotel accommodations and insurance rates for its members, while dues are very low, so they can actually save money by joining. Group leaders may also offer solidarity incentives, which provide the benefit of joining with others who have the same concerns or are similar in other ways. Some scholars suggest that people are naturally drawn to others with similar concerns. The NAACP is a civil rights groups concerned with promoting equality and eliminating discrimination based on race, and members may join to associate with others who have dealt with issues of inequality.

- Similarly, purposive incentives focus on the issues or causes promoted by the group. Someone concerned about protecting individual rights might join a group like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) because it supports the liberties guaranteed in the US Constitution, even the free expression of unpopular views. Members of the ACLU sometimes find the messages of those they defend (including Nazis and the Ku Klux Klan) deplorable, but they argue that the principle of protecting civil liberties is critical to US democracy.

- Some scholars argue that disturbance theory can explain why groups mobilize due to an event in the political, economic, or social environment. For example, in 1962, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring, a book exposing the dangers posed by pesticides such as DDT. The book served as a catalyst for individuals worried about the environment and the potential dangers of pesticides. The result was an increase in both the number of environmental interest groups, such as Greenpeace and American Rivers, and the number of members within them.

- More recently, several shooting deaths of unarmed young African American men have raised awareness of racial issues in the United States and potential problems in policing practices, including racial disparities in treatment by police officers. In 2014, Ferguson, Missouri, erupted in protests and riots following a decision not to indict Darren Wilson, a White police officer, in the fatal shooting of Michael Brown, who had allegedly been involved in a theft at a local convenience store and ended up in a dispute with the officer. The incident mobilized groups representing civil rights, such as the protestors in Figure 10.6, as well as others supporting the interests of police officers. In May 2020, George Floyd died shortly after police officer Derek Chauvin leaned his knee on Floyd’s neck for nine and half minutes, while Floyd was handcuffed and laying face down on the ground. Chauvin was later convicted of murder for the act. The protests that followed the release of video footage of the incident occurred in cities all across the United States, including Washington, DC, and were much greater—bigger, more widespread, and more significant—than the Ferguson demonstrations.